Counting Castes, Counting Controversies: Supreme Court, the Census and the OBC Question

Editorial

Nehru’s Ladder: The Unbroken Ascent of Indian Science

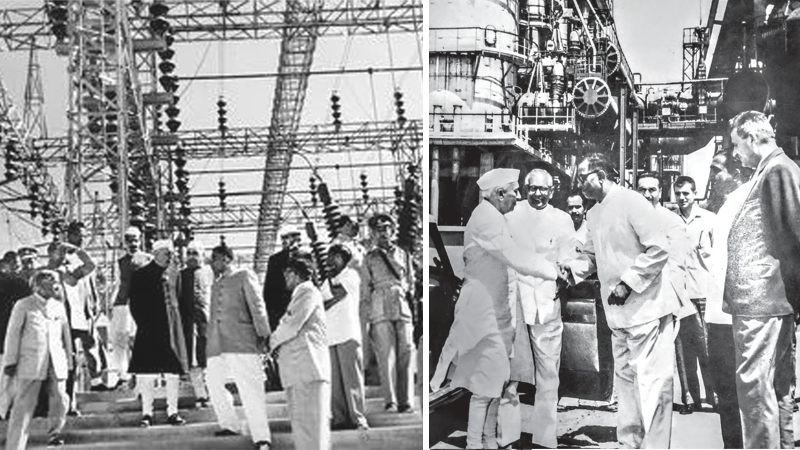

India’s scientific journey is a single, upward arc—seven decades compressed into one sturdy ladder whose first rungs were forged by Jawaharlal Nehru. He did not merely build laboratories; he embedded continuity into the nation’s DNA. The institutions he founded—IITs, CSIR, TIFR, the Atomic Energy Commission—came with two unbreakable features: autonomy and a mandate for self-reliance. Those features have survived every political storm.

The proof is in the lineage. The PSLV that soft-landed Chandrayaan-3 in 2023 traces its ancestry to the 1963 Thumba rocket. Covaxin’s viral vector was perfected in CSIR labs seeded in the 1950s. UPI’s cryptographic backbone was stress-tested on TIFR computers from the 1960s. This is not a series of lucky breaks; it is institutional compounding. A country that imported needles in 1947 now masters cryogenic engines and 5 nm lithography. The gap is filled by memory, not miracles.

Skeptics call Nehru’s model statist and slow. Yet they tap UPI on phones guided by IRNSS satellites and protected by C-DOT switches—direct descendants of his vision. The 1991 reforms did not replace the ladder; they reinforced the frame. IIT graduates who once powered Silicon Valley now fuel India’s unicorn boom. The Department of Biotechnology, born in 1986, grew from TIFR’s earliest petri dishes.

No government, whatever its hue, has dared saw off the rungs. Vajpayee’s Pokhran-II relied on BARC talent trained under Indira. The current semiconductor mission recites Nehru’s import-substitution script in a global accent. The ladder flexes but never splinters because its core beams—merit, autonomy, long-term funding—are national sacraments.

Two cracks need patching. First, the ladder’s base is uneven: elite institutes soar while state universities crumble. Second, Nehru’s temples were designed for a planned economy; today’s frontiers—AI governance, CRISPR ethics, quantum networks—require regulatory nimbleness that bureaucracy resists. The National Quantum Mission is promising, but it must swap blueprints for sandboxes.

The thesis endures. India’s S&T story is not a baton passed between regimes but a marathon run on a 1950s track. As Gaganyaan crews prepare for 2026 and Indian fabs etch sub-3 nm gates, they stride corridors whose cornerstones Nehru laid. Dams have morphed into data centers, steel towns into server farms, yet the creed—science as national faith—stands firm. Great nations do not reinvent the wheel; they keep the axle oiled.

Continuing Pollution in India: A Collective Call to Action

India’s cities—Delhi, Kanpur, Faridabad, and others—consistently rank among the world’s most polluted. The 2024 World Air Quality Report placed Delhi as the most polluted capital for the sixth consecutive year, with PM2.5 levels exceeding WHO guidelines by over 10 times. Vehicular emissions, industrial discharge, construction dust, and crop burning choke the air, while untreated sewage and plastic waste poison rivers like the Yamuna and Ganga. This crisis claims over 1.67 million lives annually, per ICMR estimates, and costs the economy $36.8 billion—1.36% of GDP. The urgency is undeniable.

Citizens’ Role in Combating Pollution

Individual action is the bedrock of change. Urban Indians must prioritize public transport, carpooling, or electric vehicles to curb the 40% of Delhi’s pollution from traffic. Switching to LED bulbs, solar heaters, and energy-efficient appliances reduces household emissions. Segregating waste at source—wet, dry, and hazardous—enables effective recycling and cuts landfill burden. Community drives to plant native trees like neem and peepal absorb CO2 and dust. Citizens can pressure local bodies through resident welfare associations to enforce bans on single-use plastics and open burning. Apps like ‘Sameer’ allow real-time air quality monitoring, empowering informed choices like limiting outdoor activity on high-AQI days.

Government’s Responsibility and Policy Gaps

The government bears the larger onus. The National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), launched in 2019, aims to reduce PM2.5 and PM10 by 20-30% by 2024 in 132 non-attainment cities—but progress is patchy. Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) measures in Delhi-NCR are reactive, not preventive. Subsidies for electric vehicles remain inadequate, with only 2% of registered vehicles electric by 2024. Industrial compliance with emission norms is lax; over 60% of red-category industries in Uttar Pradesh flout standards, per CPCB audits. Sewage treatment capacity covers just 37% of urban waste, leaving rivers toxic.

Ways and Means to Reduce Pollution

A multi-pronged strategy is essential. Short-term: Enforce strict GRAP protocols, ban diesel generators, and mechanize construction to control dust. Medium-term: Expand metro networks, incentivize EV adoption with tax rebates, and retrofit old vehicles with CNG kits. Long-term: Transition industries to cleaner fuels, enforce zero-liquid discharge, and restore urban wetlands as natural filters. Smart cities must integrate green corridors and vertical gardens. Real-time emission monitoring with public dashboards ensures transparency.

Shared Accountability

Citizens and government are two sides of the same coin. While people must adopt sustainable habits, authorities must deliver infrastructure, enforcement, and innovation. Delhi’s odd-even scheme failed without robust public transport; similarly, NCAP falters without citizen vigilance. Collaborative platforms—town halls, citizen charters—can bridge this gap. India’s polluted cities demand not just policy, but a cultural shift toward environmental stewardship. Only collective resolve can reclaim breathable skies and livable urban futures.

SAS Kirmani

SAS Kirmani